Der Speigel has published an excellent report titled The Destructive Power of the Financial Markets discussing the size and power of various players on the global financial markets.

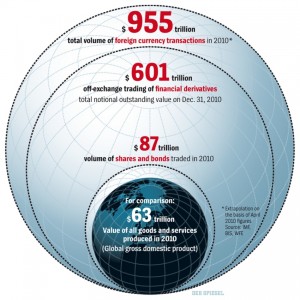

The graphic below shows the astonishing size of the global financial industry:

Click to enlarge

From the report:

The financial industry grew rapidly, as did the sums of money with which its players speculated on the prices of stocks, commodities and government bonds. The products they developed to turn money into even more money became more and more complex. At the same time, the risks they were willing to accept became incalculable.

The sector’s high salaries tend to attract the best and brightest university graduates. The members of this youthful elite don’t devise new products that make people’s lives better, nor do they found new companies that further progress. Instead, these young financial wizards invest a great deal of money and effort to develop sophisticated financial products, the sole purpose of which is to generate more profit for both their employers and, ultimately, for themselves — sometimes at the expense of other market players or even their customers.

Many things that happen on Wall Street and in London’s financial district are “socially useless,” says Lord Adair Turner, chairman of Britain’s Financial Services Authority (FSA). The values that are created there are often not real or of any use to society, Turner adds. Paul Volcker, the former chairman of the US Federal Reserve, once remarked that the only truly useful financial innovation in the past 20 years is the cash machine. (emphasis added)

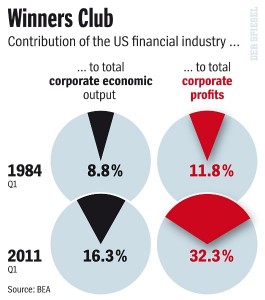

In the U.S. as the manufacturing industry was decimated in the past few decades, the financial industry gained prominence and started to account for a large portion of the economic output. By the first quarter of 2011, the industry accounted for about one-third of all corporate profits as shown in the graphic below:

Click to enlarge

Source: Der Speigel

The high reliance of the US economy on this one sector poses significant risks to the overall health of the economy. A strong economy should be diversified among many industries and not have over-concentration of just one industry.