Volatility is back with a vengeance in the US equity markets. In the first two weeks of this year stocks have been extremely volatile with the Dow taking investors on a wild ride.In times of such high volatility patience is a very important factor that differentiates successful investors from others. Panic selling and market timing does not work especially for retail investors.

Selling when the market plunges has a very high cost. Not only an investor ends up taking big losses by selling stocks are at their lows but also loses again when the market recovers strongly since that investor is usually fearful of getting back in. Moreover during panics markets plunge dramatically in a short period and during recoveries they soar violently. These types of moves are hard to predict or catch for any investor. In a collapsing market, even high quality stocks may get dumped along with others making the situation feel like that whole world is about to end. This scenario occurred during the Global Financial Crisis of 2008-2009. Since the lows from early 2009, the S&P 500 has more than doubled.

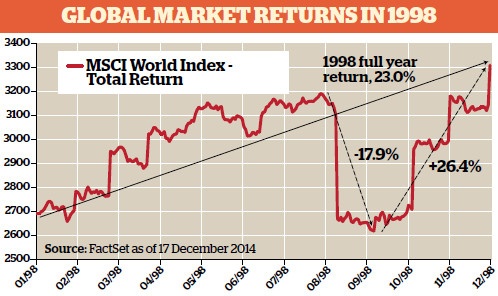

I recently came across a fascinating article by Ken Fisher of Fisher Investments on why staying calm and trusting one’s gut instincts is so important when markets are declining precipitously. He used the example of the market collapse and recovery in 1998. From the article:

Click to enlarge

In cooler moments, most investors with long-term growth goals agree they should think long term and ignore near-term wiggles. And they plan to.

But amidst volatility, more primal instincts take over – they want to take action to remove the threat of near-term pain, even if it costs them future returns. Again, investors articulate notions such as: ‘Don’t just sit there, do something’. It’s fight or flight. But sometimes doing nothing is best.

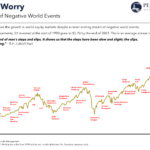

Here’s an example. 1998 was a terrific year for world stocks overall – but it was trying for investors. It started fine – world stocks rose 17 per cent by mid-July. But there was fear of contamination from the Asian financial crisis that had started in 1997 and led to Russian debt default.

Debt woes trickled west, pushing huge, super-leveraged US hedge fund Long-Term Capital Management (LTCM) to the brink of default. People feared that if LTCM failed, they could take down the US financial system, and world stocks dropped nearly 20 per cent in just 11 weeks.

But corrections move fast because they’re grounded in sentiment, not fundamentals – and sentiment changes swiftly. People got over their fears, and world stocks finished the year up a big 23 per cent overall.

Investors who ignored their gut and stayed invested were hugely rewarded. Investors who panicked and sold to stop the pain likely sold at a relative low, and probably didn’t buy back in time for the fast rebound. And they had to pay transaction fees and maybe taxes.

Source: Fisher’s financial myth-busters: you trust your gut feeling, Jan 16, 2015, Money Observer

Here is an excerpt from another article on this topic by Saket Mundra of McLean & Partners:

The mantra of ‘Doing Nothing’ stems from my belief in simplicity rather than a claim of its superiority over any other actions. ‘Doing Nothing’ marks a remarkable shift in one’s investment process from selection (finding the best stocks, forecasting the next recession etc.) to elimination (acting only on a small subset of opportunities or decisions). The decision to do nothing places the investor in a position to exploit some of the most powerful anomalies in the financial markets by:

1. Allowing only the best opportunities to make it to the portfolio

2. Lengthening the time horizon as one is not acting on short term noise

3. Minimizing the re-investment risk as the turnover is low

4. Reducing the odds of losses due to insolvency or bankruptcy4

5. Lowering the transaction costs and taxes‘Doing Nothing’ does not imply, nor is it an excuse, for complacency or poor analysis. The foundation of the theory of ‘Doing Nothing’ lies in one’s ability to eliminate mediocre opportunities, or in other words, only acting on great opportunities. The approach does not reward investors for selecting a bad business (or even a good business at a bad price) to begin with. Provided that the bulk of the analytical effort is expended before a stock is even included in the portfolio, ‘Doing Nothing’ affords the investor the luxury of ignoring short-term gyrations and focusing only on the true underlying prospects for the business, which do not change each day/week/quarter. Identifying and sticking with great opportunities not only requires unbiased and factual analysis, but a great deal of behavioral restraint as well. The lesson here is simple – when a set of good businesses are allowed to compound for a long term without intervention, the winners significantly offset the losers resulting in above average returns.

4 Kay Giesecke, Francis A. Longstaff, Stephen Schaefer, Ilya Strebulaev (2011): Corporate bond default risk: A 150-year perspective. Journal of Financial Economics

Source: ‘Doing Nothing’ – The Unloved Alternative, Aug 2014, McLean & Partners

The key takeaway is that sometimes just doing nothing and sitting tight is the most important factor. Keeping one’s emotions in check and being focused on the long-term goal will lead to better investment returns. In today’s world of text alerts, email alerts, 24/7 internet connectivity, smartphones, 24/7 TV news, etc. it is very difficult to do nothing for most of us. But to be a successful investors requires sacrifices and one sacrifice that investors must do during times of market corrections is simply to became a spectator of all the actions and not become a participant.