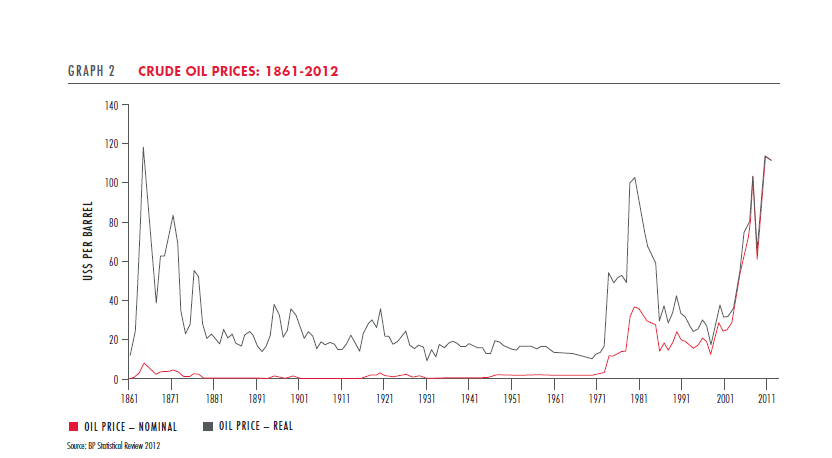

Crude oil prices(WTI) closed at $103.84 on Oct 4, 2013. Prices fell below $50.0 per barrel at the peak of the global financial crisis but has recovered to stay in the $100 range in the past few years.

The following chart shows crude oil prices in both nominal and real terms from 1861 to 2012:

Click to enlarge

Source: Sasol: A history of underestimation, Rory Kutisker-Jacobson, Allan Gray

While prices remained stable for years after 1971 it took off. Since 2000 prices have soared to astronomical levels.

From the article:

The question then becomes: Why is the oil price high, and, more importantly, is a significant decline in the future likely?

Unlike many commodities, the oil market is somewhat unique in that the swing producer is one of the lowest cost producers. Roughly 43% of world production comes from the Organisation of the Petroleum Exporting Countries (OPEC), with Saudi Arabia being the largest producer. Saudi Arabia is also the only OPEC country with significant spare capacity. While the pure cost of extraction in Saudi Arabia is low, the vast majority of government revenue is derived from the sale of oil, which is used to subsidise other industries and social welfare. Current estimates are that Saudi Arabia needs an oil price of between US$90 and US$100 per barrel to balance its fiscal budget. It is in the Saudis’ best interests to manage the supply of oil to maximise their revenue per barrel without encouraging demand destruction.

The formation of cartels is illegal in all industries except OPEC. This cartel for the most part determines the price of oil in the global market. Here is a definition of cartel from Wikipedia:

A cartel is a formal (explicit) “agreement” among competing firms. It is a formal organization of producers and manufacturers that agree to fix prices, marketing, and production.

It is interesting how countries such as Saudi Arabia are legally allowed to manipulate the prices in order to balance its budget.

Related ETFs:

- United States Oil (USO)

Disclosure: No Positions