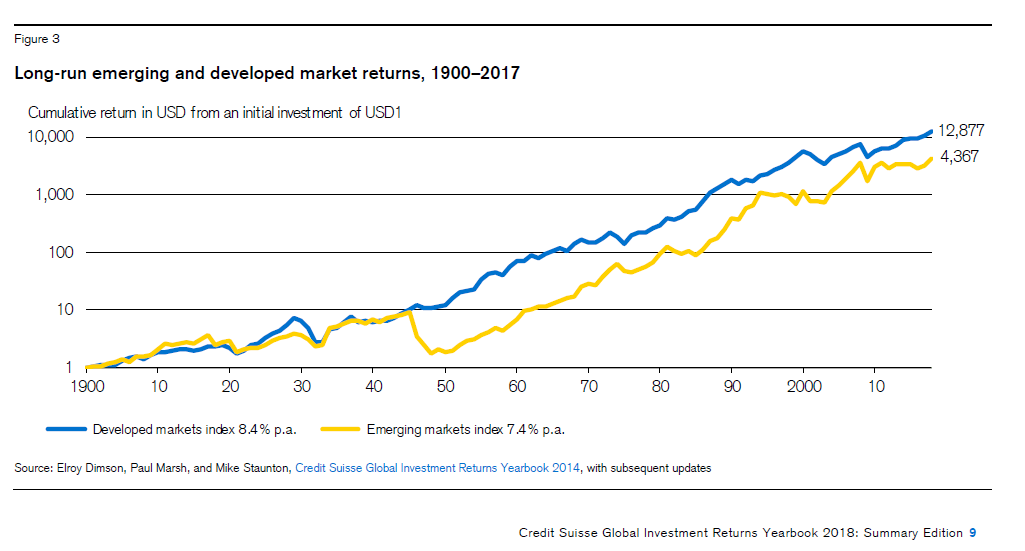

One of the easiest and simplest diversification strategies is to diversify across borders.Since the performance of equity markets varies across countries in any given year, an investor can boost their returns by spreading their assets across many countries. For example, emerging markets that are highly dependent on commodity exports perform well when commodity markets boom. By diversifying between developed markets and these emerging markets, investors can earn higher returns.

In addition, no one country’s equity market is the top performing market year after year. For example, Canada was the best performer in 2016 but ended up being the worst in 2017 due to decline in energy prices.

The following quilt from Schwab shows the importance of allocating assets across countries:

Click to enlarge

Source: Why Global Diversification Matters by Anthony Davidow, Charles Schwab