U.S. companies are hoarding almost $1 Trillion in cash and cash equivalents in their balance sheets according to a Bloomberg report. Despite the sluggish economic recovery companies are fearful of putting this money to work.

The S&P states: “The second quarter of 2010 marked the sixth straight quarter of record cash levels, amounting to $842 billion for companies in the S&P 500 Industrials index (which excludes financial, transportation, and utility issues).” U.S. companies are earning record-high profits in recent quarters as a result of many of the cost-cutting efforts deployed after the credit crisis and the massive layoffs.

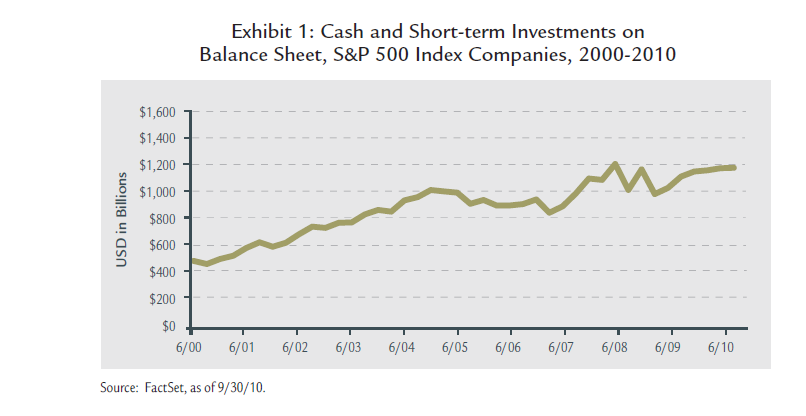

The chart below shows the growth of cash and cash equivalents of the S&P Index companies since 2000:

Click to enlarge

Source: Dividend Yield: The Implications of Cash Sitting on Balance Sheets, The Brandes Institute

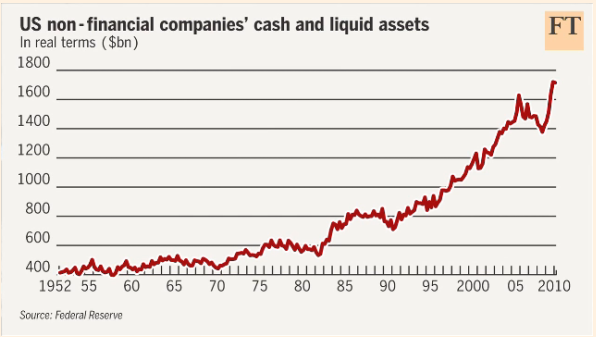

This is not the first time that U.S. companies are hoarding huge amounts of cash. According to an article by Barry Riholtz back in July, corporate cash been piling up since 1982. From the article:

“The average cash-to-assets ratio for corporations more than doubled from 1980 to 2004. The increase was from 10.5% to 24% over that 24 year period. That was the findings of a 2006 study by professors Thomas W. Bates and Kathleen M. Kahle (University of Arizona) and René M. Stulz (Ohio State). When looking for an explanation, the professors found that the biggest was an increase in risk.

Indeed, the phenomena of corporate cash piling up has been going on for a long long time. You can date it back to the beginning of the great bull market in 1982 to 86, went sideways til the end of the 1990 recession. It has been straight up since then, peaking with the Real Estate market in 2006. The financial crisis caused a major drop in the amount of accumulated cash, but it has since resumed its upwards climb.

This FT chart makes it readily apparent that this is not a new trend: ”

Source: FT

Among the various sectors, S&P research showed that companies in the IT, oil, and health care industries have accumulated especially huge amounts of cash in recent months.For example, by mid-year Apple Computer (AAPL) and Google (GOOG) had $24 billion and $30 billion, respectively. In the oil sector, industry giant ExxonMobil (XOM) had $13.3 billion in cash and cash equivalents. Some of the other firms with huge cash hoardings include GE(GE), Microsoft (MSFT), Cisco(CSCO), Johnson & Johnson(JNJ), Verizon(VZ), Altria(MO), Disney(DIS), Oracle(ORCL),etc.

What do companies do with excess cash?

Some of the options available for companies to to deploy excess cash are increase dividend payments, acquire other firms, buyback own shares, reinvest in operations or simply retain the cash in the form of cash or short-term marketable securities.

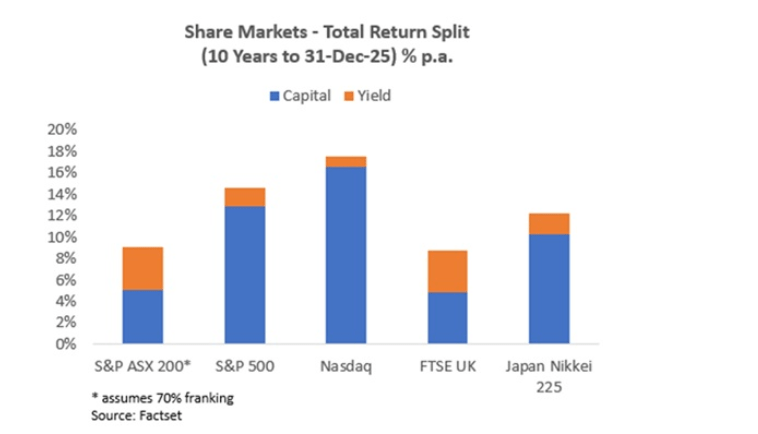

Increasing dividends is one of the simplest ways companies can spend their excess cash that is advantageous to shareholders. The current dividend yield on the S&P 500 is about 2%. This is much lower than many other developed markets. Countries such as UK, Australia, New Zealand, France, Italy, Spain, etc. traditionally have much higher dividend yields. For example, Australia has a dividend yield of about 4%.

In recent months many companies such as Nike, Intel, Baxter, UPS, Johnson Controls, etc. have announced dividend raises. But despite this increase, U.S. companies have lower dividend yields. The following table consisting of randomly selected stocks shows that the majority of firms across a range of industries have yields of less than 5%:

[TABLE=755]

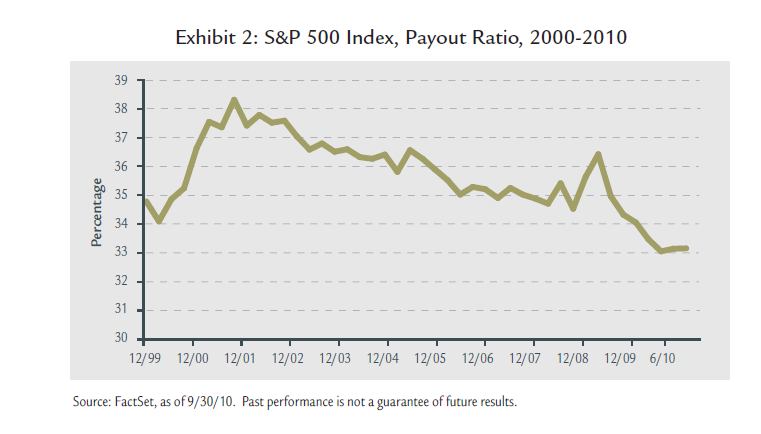

In addition, even though companies are sitting on mountains of cash, the payout ratio of S&P 500 is still lower than the average for the past 10 years as as shown in the graph below:

Click to enlarge

Source: Dividend Yield: The Implications of Cash Sitting on Balance Sheets, The Brandes Institute

Many foreign companies have much higher payout ratios sometimes exceeding 40%.

Since U.S. companies have the cash and the capacity to raise dividends they should raise dividend payouts significantly now. Increasing dividends would also put them on par with their foreign peers. Some may say that taxes may increase on dividends in 2011 if Congress does not extend the current low rates on them. However even if higher taxes are levied on dividends it is beneficial for investors to earn higher dividends if companies are unable to use them productively and investors would be able to use the cash as they wish.

Large piles of cash on their books makes some companies spend them in ways that negatively impact shareholders such as when companies overpay for their acquisition targets, hand out more in executive compensation, etc. Case in point: Amazon recently bought diapers.com paying $500 million in cash and assuming $50 million in debt.

Another way that companies spend their excess cash is buyback their shares. European companies rarely implement share buybacks. American companies tend to follow this option often since it is easy to impact share prices in the short-term without much effort. This strategy has been proven in many studies to be detrimental to shareholders. In fact companies that authorize buybacks do not know how to deploy their cash efficiently and simply decide to buy back shares. One of the arguments supporting this idea is that they consider their shares to be cheap. Usually when a buyback program is implemented, it gives a short-term pop to stock prices. When that happens, executives tend to exercise their options and sell shares. Only in some cases do share buybacks reduces the float. When companies approve share buybacks some investors consider that to be an indication that the management of the firm is incompetent since they do not know how to grow the company such as doing an M&A deal, investing in R&D, etc.

Companies also buy back shares to help offset the dilutive effects of expiring stock options. A study by S&P found that of the 214 companies in the S&P 500 that did buybacks in the fourth quarter of 2009, just 50 actually resulted in share-count reduction. This indicates that the rest engaged in buybacks just to match them with expiring options.

From an article in Bloomberg BusinessWeek on share buybacks:

“Yet for all its success, perhaps the ripest investment opportunity IBM sees is its own stock. The Armonk (N.Y.)-based company announced on Oct. 26 that it plans to buy back an additional $10 billion of its shares—and has said it plans to spend about $50 billion on buybacks in the next five years. Since taking over as chief executive officer in 2002, Samuel J. Palmisano has spent more than $68 billion on buybacks, about 38 percent of IBM’s current market value. Over that time, only ExxonMobil (XOM) and Microsoft (MSFT) have bought more of their own stock. IBM has 1.24 billion shares outstanding, down from 1.72 billion at the beginning of 2003.”

Many investors would agree that spending $50 billion of shareholder’s equity on buybacks is not a good strategy.

The article further added:

“One objection to buybacks is that companies may overpay, with cash that might be deployed more strategically. From 1986 through 2002, General Motors spent $20 billion on buybacks with money that should have gone to shoring up its finances, says William Lazonick, director of the Center for Industrial Competitiveness at the University of Massachusetts Lowell. In the past decade, Microsoft spent more than $103 billion on buybacks; its stock trades at about half its 2000 high. “A lot of companies are just stupid about buybacks,” says Niles. “There should only be one reason you buy back shares: You think they’re going up.”

At $143.84 on Nov. 2, IBM stock was up nearly 10 percent for the year to an all-time high. Still, David Trainer of New Constructs, a Brentwood (Tenn.) investment research firm, thinks it is undervalued. IBM has steadily raised profits to more than $10 a share, from $3.07 a share in 2002. It has said it aims for operating earnings of $20 a share by 2015. Yet the stock is “trading as if the company’s profits will stay the same forever,” says Trainer, who bases his analysis on IBM’s book value and cost of capital. “Buying back stock is management’s way of signaling to shareholders that the stock is cheap.” Mike Fay, an IBM spokesman, declined to comment.

Some would like to see IBM use the buyback money on dividends. “The profit is the shareholders’ money,” says Eddy Elfenbein, who runs the blog CrossingWallStreet.com. IBM’s 1.81 percent dividend yield trails the S&P 500 average of 1.92 percent. Microsoft yields 2.34 percent; Intel (INTC), 3.10 percent. “With yields at historic lows and CDs paying nothing,” says Joshua Scheinker, a senior vice-president with Janney Montgomery Scott in Baltimore, “everyone wants to see an income stream.” Scheinker notes that dividends are taxable—and that the levy may rise if Congress does not extend the Bush tax cuts.”

It is true that many of the companies that have excess cash such as IBM carry debt on their books. They can use the excess cash to pay down debt. But companies seem to have decided not to pay down debt now since they can use the cash to reinvest in their operations or they simply want to hold onto cash for now until the economy recovers.

In conclusion, for the reasons discussed above US stocks will become more attractive to investors if they increase their dividend payments further from current levels.