The size of the U.S. economy is about $14.66 Trillion. However over 70% of the GDP is based on consumption spending. As a result any recovery is highly dependent on the U.S. consumer whose household debt is still too high by historical standards. This is in sharp contrast to U.S. companies which hold over $1.0 Trillion in cash and cash equivalents on their balance sheets. With the official unemployment rate at 9.1% in August, millions of unemployed Americans are unable to contribute much to an economic recovery due to reduced spending.

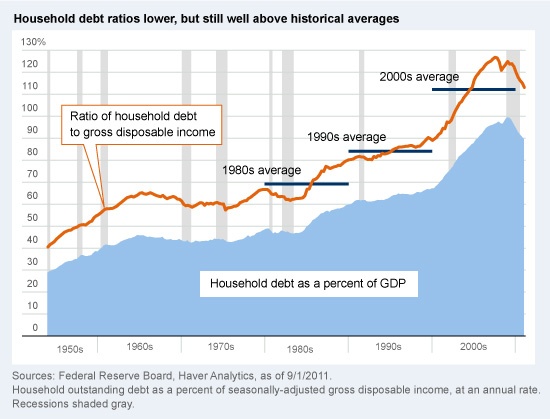

According to a Federal Reserve Bank study, the U.S. ratio of household debt-to-disposable income was 147.2% during the third quarter of 2010. This is still higher than historical averages as shown in the following graph:

Source: The albatross on economic growth, Fidelity Investments

From the research article:

After peaking at $13.9 trillion in the first quarter of 2008, overall household debt has fallen by $608 billion—but what really matters is household debt relative to personal income. Measuring debt levels relative to a person’s income gives a better indication of the capacity to spend. Using the ratio of total household debt to gross disposable income, it is striking how quickly the average household piled on debt in the 2000s.7

From 1952 to 1979, the average ratio of household debt to gross disposable income was 57%, but over the past three decades the averages steadily, and then dramatically, climbed higher. In the 1980s, it averaged 69%; in the 1990s it averaged 84%; but then the housing boom hit in the 2000s and the ratio skyrocketed to an average of 112%. The ratio ultimately peaked in Q3 2007 at 127%, right before the onset of the recession.8

While the household-debt-to-disposable-income ratio has come down to 113%, there is still a way to go to reach the lower levels of the 1980s or ’90s. Given the level of gross disposable income at the end of Q1, overall household debt would need to fall another $3.4 trillion to match the average debt-to-disposable-income ratio of 84% from the 1990s.

It will be a long slog to get household debt back to more sustainable levels—a process made all the more difficult and painful by the slow growth in personal income. As long as household debt levels remain high, deflationary pressures will likely remain a headwind to consumer spending, and thus to economic growth.