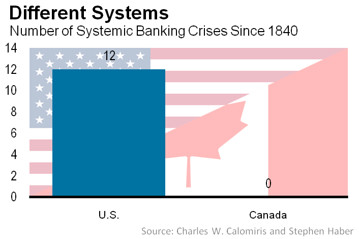

I came across a fascinating Journal article that I had bookmarked before in 2013 on banking crises in Canada and the US.

Since 1790, the United States has suffered 16 banking crises. Canada has experienced zero — not even during the Great Depression.

Source: Why Canada Can Avoid Banking Crises and U.S. Can’t, WSJ, Apr 9, 2013

From the article:

That anti-populist political system — known in political science as liberal constitutionalism or liberal democracy — is a key ingredient in Canada’s stable banking track record, Mr. Calomiris contends in his paper, which is a summary of a much longer book he’s written with Stephen Haber due out in September. That’s because this kind of political system makes it difficult for political majorities to gain control of the banking system for their own purposes, the authors contend.

Populist democracies like the U.S., on the other hand, tend to create dysfunctional banking systems because a majority of citizens gain control over banking regulation that steers credit to themselves and to their friends at the expense of the citizens that are excluded from the banking system, he said.

The contrast between the U.S. and Canada was part of Mr. Calomiris broader argument that dysfunctional banking systems — which are by far the norm rather than the exception around the world — are the result of political factors.

“Whether societies have dysfunctional banking systems is really not a technical issue at all. It’s a political issue,” Mr. Calomiris said at the conference, introducing his premise as “we do know how to avoid dysfunctional banking but that we make political choices – you might even say consciously” not to have functional banking systems for most of the modern era in most countries of the world.

The history of the U.S. banking system is one in which the government forms partnerships with different interest groups at different points in history, and those coalitions jointly influenced the way the banking system was regulated, Mr. Calomiris argues.

“In populist democracies, such as the United States, the regulation of banking is used as a political tool to favor some parties over others. It is not that the dominant political coalition in charge of banking policy desires instability, per se, but rather, that it is willing to tolerate instability as the price for obtaining the benefits that it extracts from controlling banking regulation,” he writes in his paper.

Other ountries that have been crisis free are Singapore, Malta, Hong Kong, New Zealand and Australia.

Here are some exceprts from a NBER paper related to this topic:

When European and North American banks teetered on the brink of meltdown in 2008, requiring bailouts and extraordinary central bank intervention, Canadian banks escaped relatively unscathed. History explains why, according to co-authors Michael Bordo, Angela Redish, and Hugh Rockoff in Why Didn’t Canada Have a Banking Crisis in 2008 (or in 1930, or 1907, or …)? (NBER Working Paper No. 17312). Starting in the nineteenth century, Canada and the United States took divergent paths: Canada set up a concentrated banking system that controlled mortgage lending and investment banking under the watchful eye of a single, strong regulator. The United States allowed a weak, fragmented system to develop, with far more small (and less stable) banks, along with a shadow banking system of less-regulated securities markets, investment banks, and money market funds overseen by a group of competing regulators.

“[T]he stability of the Canadian banking system is not a one-off event,” the authors note. “In Canada the banking system was created as a system of large financial institutions whose size and diversification enhanced their robustness…. In the [United States] the fragmented nature of the banking system created financial institutions that were small and fragile. In response the [United States] developed strong financial markets and a labyrinthine set of regulations for financial institutions.”

The contrast is striking. While in 2008 and 2009 the United States experienced bank failures, bailouts, and the worst recession since the 1930s, Canada had no bank failures, no bailouts, and its recession was less severe than either that of the early 1980s or early 1990s. Long before 2008 in the United States, there were the failures of the private investment bank Jay Cooke and Co. (the 1873 crisis), the Knickerbocker Trust (the 1907 panic), and the runs on banks that deepened the Great Depression. Although Canada’s economy suffered a collapse equally as dramatic as America’s in the 1930s, not one of its banks failed.

“The twin weaknesses of the American financial system — a commercial banking system divided along state lines and volatile financial markets in which a ‘shadow banking system’ of unregulated or lightly regulated investment banks and other financial intermediaries participated — produced a series of financial panics,” the authors write. “There were major banking panics in 1837, 1857, 1873, 1893, and 1907, and minor panics in 1839, 1884, and 1890.”

Source: Why Canada Didn’t Have a Banking Crisis in 2008, NBER

The entire journal article and the NBER paper is worth a read.